“When you see this moonshiner half-drunk and asleep, the fact is he was working,” Jim says. “I have a tremendous amount of respect for them. I know how much work it is with electricity and pumps. One old moonshiner I talked to—his job was to carry water up a hill and pour it on that coil for eight hours.”

When the age of the revenuer came and the demands of prohibition increased production, the process changed again. Moonshining became an enterprise. Clandestine methods took on new twists. Technology and enterprise found investors and collaborators.

In the Ozarks, it nestled up to ranchers and bakers. These legitimate businesses could acquire the corn, sugar, and yeast in quantity without raising suspicions. Often they got paid in moonshine for their trouble. This is the era that lingers in our cultural memory. These are the stories swapped by old-timers, who still wander into his shop, wondering what Jim is up to and willing to share their tales.

“I’ve always been fascinated by it, and I always listen,” Jim says. “They want to see if I’m doing it right. They want to taste mine, and I want to hear their stories.” Today everything is legal, resulting in a mountain of paperwork. Because of varying alcohol content within the spirits, the accounting can be a bit of a hassle.

Now they use a hydrometer to check the strength of the spirit. In the old days though, they used fire. The term “100 Proof” refers to the fact that at 50 percent alcohol content, the liquid would sustain a combustion of gunpowder, offering assurance that the alcohol was there.

Even at Copper Run, the romantic notion and whiff of the historic illicit activity lingers and draws people from miles away. Dino Neis, a tour-bus driver from Minnesota, made a side trip while transporting a tour group. When he heard there was a place to get genuine Ozarks Moonshine, he left a load of ladies at a theater in Branson and scooted back up the road for a visit.

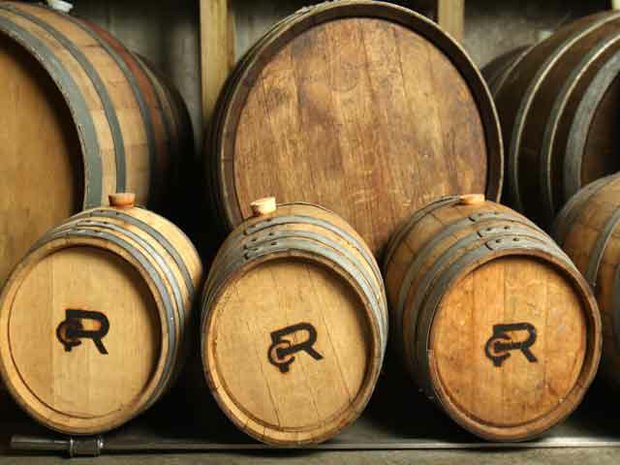

Dino has toured all the big distilleries, but Copper Run offers a connection to spirits that a large distillery just can’t match. “For one thing, the barrel room here is nine barrels,” Dino says. “You have a much more hands-on experience. When you have millions of barrels going, you can’t test all of them. I like the craftsmanship of it.” The popularity of the product has created something of a production bottleneck.

When people hear about Copper Run, they stop. When they stop, they buy. Jim’s plans to age his whiskey into bourbon have been hampered by the fact that he can sell the moonshine and whiskey a lot faster than he was expecting, and expansion is under way. A new deck and shop are planned, as well as space for increased production. A vodka product is on the horizon for Copper Run as well as a fruit-flavored moonshine using local fruit.

You can also age your own spirits with the Copper Run Barrel Guild. You can purchase one-gallon, three-gallon, five-gallon, and 10-gallon barrels to start aging your own bourbon directly from Copper Run.

“Sippin’ History At Copper Run” by Sandy Clark, photo by Mark Scheifelbein.